Card Fees vs. Cost of Capital: A Realistic Framework for Payment Decisions

In discussions about B2B payments, one argument comes up again and again: “accepting card payments is expensive.”

That statement is not wrong — but it is incomplete.

What is often missing from the conversation is the economic alternative: when a supplier is not paid immediately, it is effectively financing its customer. That financing has a real cost, driven by payment terms and the supplier’s cost of capital.

In this article, we take a deliberately realistic approach. Rather than debating theory, we anchor the analysis in observed U.S. payment behavior and practical capital costs, and then progressively expand the framework to reflect how finance actually works in the real world.

1. Payment terms: what actually happens in practice

Many analyses implicitly assume Net‑30 terms. In reality, U.S. suppliers operate across a much wider range of payment terms.

According to survey data published by the Center of Advanced Purchasing and Supply (CAPS), payment terms in the United States manufacturing sector are distributed as follows:

| Payment Terms | Share of Companies |

|---|---|

| 30 days | 24% |

| 45 days | 38% |

| 65 days | 27% |

| 90 days | 11% |

The key takeaway is simple: most invoices are paid at or beyond 45 days, and a meaningful share stretch to 60 or even 90 days. Any serious comparison between invoicing and card payments must start from this reality.

2. Cost of capital: not all balance sheets are equal

The second input is the supplier’s cost of capital — the economic cost of tying up cash while waiting to be paid.

While exact figures vary by business, a realistic U.S. distribution looks roughly like this:

| Cost of Capital | Typical Business Profile |

|---|---|

| 6% | Large, investment‑grade enterprises |

| 10% | Strong mid‑market companies |

| 15% | Typical SMB |

| 20%+ | Cash‑constrained SMBs and contractors |

Because the U.S. economy is overwhelmingly composed of small and mid‑sized businesses, double‑digit cost of capital is the norm, not the exception.

3. A first‑order comparison: cards vs invoices on capital cost alone

Let’s now compare two options for a $1,000 transaction, purely on the basis of cost of capital and payment terms.

Assumptions (intentionally simple):

Card payment cost (U.S. average): 2.5% = $25, paid immediately

Invoice payment: no fee, but cash is received after 30–90 days

Cost of capital varies from 6% to 20%

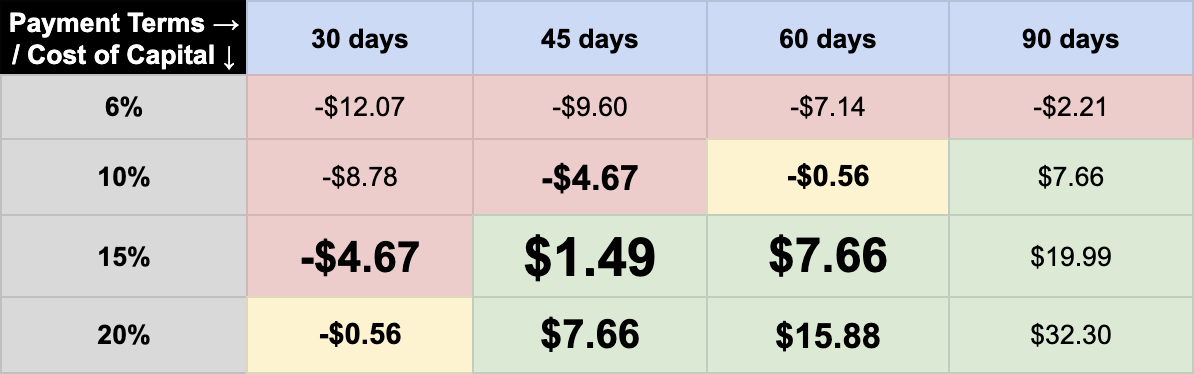

The table below shows the difference in cost between being paid by invoice versus card:

Δ = Invoice financing cost – Card fee

Negative = invoice cheaper | Positive = card cheaper

What this tells us:

With short terms and cheap capital, invoicing is economically cheaper

As terms lengthen and capital costs rise, card payments quickly reach — and pass — the break‑even point

Even at this first step, the conclusion is already more nuanced than “cards are expensive.”

4. Expanding the lens: processing costs also matter

However, this view is still incomplete.

Invoices are not free to issue, track, reconcile, and close. Likewise, card payments are not free to capture and reconcile on the revenue side. To be realistic, both must be included.

Typical processing costs (conservative benchmarks)

Invoice handling: ~$10 per invoice (creation, delivery, reconciliation, exceptions)

Card revenue capture: ~$2 per transaction (settlement files, reconciliation)

Updating the comparison:

Total card cost: $27

Total invoice cost: financing cost + $10

This shifts the economics meaningfully.

Break‑even now moves materially earlier:

At ~15% cost of capital, card payments are already cheaper at 45 days

At ~20%, card payments win even at Net‑30

5. Re‑introducing realism: where most U.S. businesses actually sit

When we combine:

CAPS payment‑term distribution (most invoices ≥45 days)

The fact that most U.S. businesses operate with 15–20% effective cost of capital

…the center of gravity shifts decisively.

Note: font size represents relative prevalence of each scenario; it does not change the underlying economics.

For the median U.S. supplier, invoicing is not cheaper — it is simply slower and hides its cost in working capital and operations.

This does not mean cards are always the right answer. It means that the default assumption that invoices are economically superior is no longer valid for a large share of the market.

6. What else should factor into the decision

A complete decision framework should also consider:

Cash‑flow volatility and liquidity risk

Late payments and disputes, not just stated terms

Administrative overhead beyond average processing costs

Buyer behavior and compliance

Rebate economics on card volume

Growth constraints caused by trapped working capital

Just as importantly:

Cost of capital can be improved (balance sheet strength, financing strategy)

Card fees can be negotiated (volume, network mix, acquirer relationships)

Results vary significantly by country, where interchange and payment norms differ

7. A more useful question

Rather than asking:

“Are card fees expensive?”

A more financially accurate question is:

“Is our cost of capital — at our actual payment terms — lower than the cost of getting paid instantly?”

For a growing share of U.S. businesses, the honest answer is increasingly no.

That is not a payments debate. It is a capital efficiency discussion — and one worth having explicitly.